From School to Unschool: My Journey as an Educator Unlearning How to Teach

- Dara Hutchinson

- Mar 31, 2023

- 18 min read

Updated: Jun 27, 2024

Seven blog posts later, I think I have brought y'all up to speed on our personal backstory! It was cathartic for me to write it all out, yes, but I also think it was necessary to share openly about the intensity of our experience to help everyone understand that the journey to unschooling is rarely an easy road. A few unschooling families may plan their children's education to look like this from the start, but I think the majority of us fall into self-directed learning only after making the difficult realization that traditional education, even traditional school at home, isn't the right fit for our children. For my family, it was certainly more of a last resort than an initial plan. I only discovered the beauty of this lifestyle as time passed and I witnessed my son's learning unfold in a natural, unstoppable way as we went about our lives. But it doesn't have to be a last resort! You can choose this life at any point.

That's why I'm hoping this blog will be helpful. To build your confidence about what is possible when unschooling. To understand how different it looks.

The examples of learning for an unschooling family are interwoven so tightly with daily life it might not feel like education at all. Indeed, that's probably the goal. But as parents new to this approach, we worry. How will they actually learn anything?! I was especially concerned about the foundations of literacy and numeracy. Students in my classes always had ample time to play in rich environments, just like E did, but in my classroom, I also assessed my students' reading levels with 1:1 testing, I met with math and literacy small groups for hands-on lessons, we had set time for open-ended math and literacy exploration, I asked them to show me what they know with unaided writing that I would then assess with a rubric, I had colleagues I could consult with. My son wouldn't let me do any of that at home! How was I going to teach him anything? How would I know he was learning?

This post will share my gradual, years-long shift from assuming homeschool would mean recreating my classroom at home, to surrendering to the fact that what E needed, completely self-directed education, would mean unlearning much of what I assumed to be true about the role of an educator, and relearning my role as the parent of an unschooler.

This is me, 24-years old, at the beginning of my teaching practicum in 2009.

This person could not at all have imagined that in 14 years she would be unschooling her neurodivergent children, living in a new country, and healing from parental PTSD. But here we are!

So, this is the story of how E and I came to be unschoolers. When E was an infant and toddler, we played, we read, we sang, we baked, we went on adventures.

Life was learning at that age, and for a very young child, that is natural and easy for our society to accept. It's strange how it shifts so quickly as a child becomes a preschooler - even the term preschooler assumes the child will be in preschool. What does it look like if they are not?

When E was three and I decided I didn't care for any of the early childhood education options in our city (and I recognize what a privilege it is to be able to make the choice to keep my child at home - it worked for our family at that point because when we first moved to the states, I only had a dependent visa not a work visa, so I couldn't have gone back to work anyways), I thought I "should" be doing something more structured with him since many (most?) of his peers would be at daycare or early childhood programs at least some of the time. Honestly, in retrospect, E would have been just fine continuing to play together and explore as we had been doing all his life, but by this time I was craving some structure.

A friend introduced me to the Whole Family Rhythms Seasonal Guides by Meghan Rose Wilson (Meghan has since shifted the focus of her work and I don't believe the guides are available to download on her site anymore, though you may be able to find them elsewhere online). The seasonal guides were exactly what I was looking for to create a steady rhythm for E and myself at home, while also giving us ample freedom to still do our own thing.

The guides provided one adult-led activity each day, inspired by a weekly nature-inspired theme. They also suggested ways to structure your daily life with young children to allow for natural ebbs and flows of energy, balancing in-breaths to restore and connect with out-breaths for lively play and excitement. Moreover, there were weekly meditations for caregivers, instructions for caregiver handiwork projects, picture book lists, and more, and it was all rooted in the natural rhythms of the seasons. I loved it.

As with any resource, however, you hold on to what resonates for you and let the rest go, like flour through a sieve. We never followed everything in the guides exactly as written. I realize now I was already making autonomy and choice accommodations for E; for example, instead of having a steady rhythm of the same adult-led activity on the same day of the week each week (like Tuesday is always a painting day), I quickly adjusted to letting him choose our activity for the day because that was more successful for us, plus have him choose the type of paint we would use, or whether we would model with beeswax or playdough or clay. The guides assumed it would be neurotypical children happily going along with every adult demand. At age 3, that already was not working for us.

Our parent-led activity choices were painting, crafting and modeling, then we had one day at our music class, and one day at Forest School. It was a good balance of home time and outings, for me anyways. I realize now that E's experience of the world is so much more intense and overwhelming than mine. He has so much more information to process sensorially, socially, that he was likely internalizing a lot of nervous system activation at this time, leading to the meltdowns and aggression we were starting to see at home, but I hadn't made the connection yet between demands and behaviour. I was treating him like a neurotypical child, because we had no indication yet that he was not.

When E was four and preschool didn't work, I again thought I "should" be doing more math and literacy activities with him so he wouldn't "fall behind." At this point, I could still set out school time activities to introduce and reinforce foundational concepts without triggering his threat response. I realize now that my activities worked for him for PreK because they were open ended enough to allow him the autonomy he needed. And the idea of "school time" was still novel. Also, in retrospect, his window of tolerance was not quite yet razor thin, so he had enough capacity to take part in my invitations without it putting him into fight-or-flight. I was excited to plan out our preschool days! As you can tell from my planning binder, I was more than happy to jump back into my role as a teacher with my one lovely pupil!

From the time he was about five (when B was a baby, the pandemic was in full swing, and E was entering burnout - though we didn't know the term yet), any situation where I was the "teacher" triggered his threat response in an externalized way. For his kindergarten homeschool year, I had optimistically planned out our school time to include all the best elements of my classroom teaching. I even created at home versions of a shape of the day and used a weekly lesson plan template almost identical to my classroom days.

I knew exactly how to teach kindergarten. I have a master's in early childhood education. I was so confused when E couldn't participate how I expected in any of my lessons. These were wonderful, rich, meaningful activities that had gone over well with my classroom students for years. I'm pretty sure he ripped down that shape of the day after about two days, and I abandoned my weekly planning by about October, if not before.

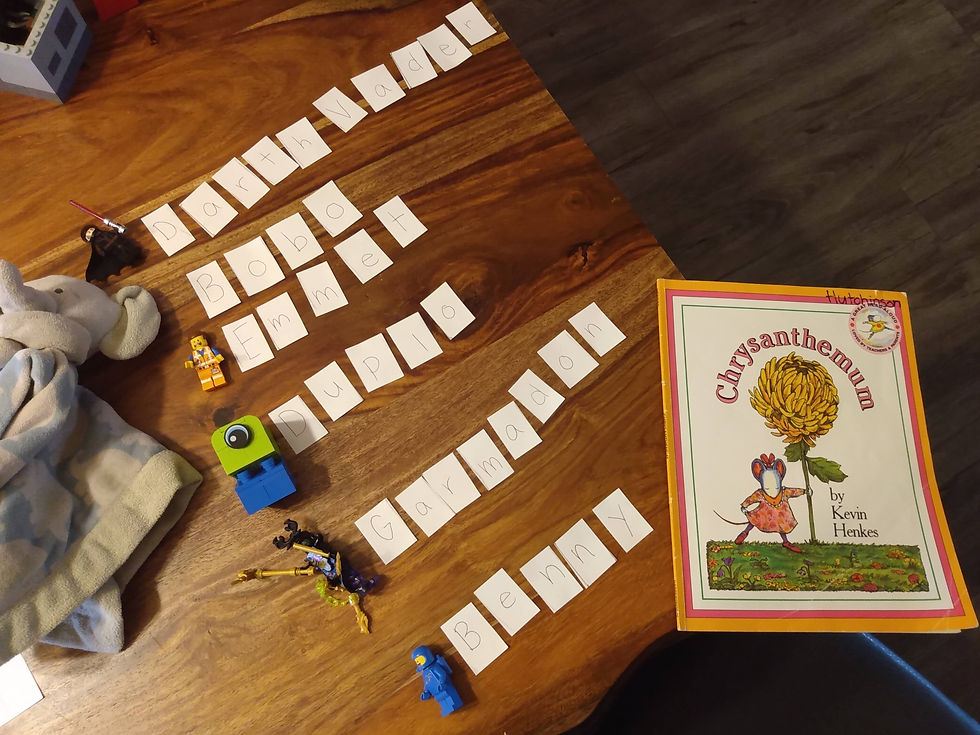

At the beginning of kindergarten, in the best case scenario, he would adapt my activities so he could feel more in control. For example, I recreated a lovely beginning of the year lesson inspired by Kevin Henkes' sweet book Chrysanthemum where in my classroom we would write out all the names of the students and create a name graph together to be put on display. I thought E and I could do the same with the members of our family, but E insisted we use the names of some of his Lego figures and his lovey instead. Sure, why not!

Or the time I had set out a salt tray as an invitation to practice forming letters and numbers with a paint brush, always a favourite in my classroom, and he wrote one number then decided the salt reminded him of the snowy terrain from the planet of Hoth, so he spent the next hour playing with the salt and his Star Wars Lego. Ok, great! That's some impressive connecting, I suppose!

Or the time I thought it would be fun if we did another one of my kindergarten favourites, a monthly self-portrait where we study ourselves with mirrors and draw what we see and then compile the monthly portraits into a book at the end of the year. The day I explained that project, he decided that Benny the 1980's Spaceman would do a self-portrait instead. Didn't Benny do a great job?

Or the time I wanted us to make a number line to display in our play area as a reference and I suggested we take pictures of E's fingers holding up the right amount of fingers for each number. Co-creating alphabet and number lines and other classroom decor with my students each year was a lovely way to give them ownership over our classroom environment. E was into the idea, but wanted to wear mittens for the photos. I confusedly explained how that would make it hard to see his fingers; he is a very bright child and this idea seemed so odd. So, instead, he decided to colour all over his hands to make marker mittens. I realize now that insisting on the marker mittens was him levelling with me in order to be able to feel regulated enough to go along with the activity.

These are just a few examples of how, even when his threat response was only mildly activated, he still could not handle any school-related activity without compensating somehow to regain balance with me. At the time, I didn't even know about levelling/equalizing/compensation behaviour (I learned much more about it when I took Kristy Forbes' In Tune with PDA course), but I went along with his creativity because to do otherwise would often have meant a meltdown, and I did recognize that his ideas were fascinating! And really, what did it matter? He was still learning. But I was certainly confused.

At the other end of the regulation spectrum, school time activities also sometimes resulted in a trashed play area, ripped books, posters stripped from the walls, pencils snapped in two and hurled across the room, or even a simple, "Meh. This is kind of boring. I'm going back to my room." (But I have much fewer photos of those days!)

So, throughout his kindergarten year, I was instinctively letting E's interests lead our learning more and more. After a few months of trying and failing to homeschool just like I had taught in public school, I stopped trying to recreate school at home. Instead of "school time" when the baby had her morning nap, we would play Lego together or pick a boardgame or card game. (I have since learned this is actually a name for homeschooling through boardgames - gameschooling!) Lego and games have long been deep interests of E's, and they are both interests he shares with my husband as well. Both are wonderful pastimes to learn through, I must say.

He also made so many connections between one of his other deep interests at the time, Star Wars, and ... pretty much everything else in our life. Star Wars was the inspiration for puppets, for Lego, for clay creations, for writing, for drawings, and more!

He still enjoyed me reading aloud to him at that point and would often build Lego creations inspired by our books. He made this not long after we read the original Wizard of Oz. From left to right, Tin Man, Toto, Dorothy, Lion, Scarecrow, The Wizard of Oz, all staged in front of The Emerald City.

Instead of having writing time where I would model emergent writing in a mini lesson and then expect him to write in his writing book, he would just get out the art supplies when he felt like it and naturally included emergent literacy concepts, like labels, titles, and speech bubbles, in his creations, asking me for specific help in the moment if he needed it; those teachable moments were much more memorable for him because they were driven by writing that he wanted to do. As my sister once reminded me (she's also a teacher), it's amazing what kids will write when they feel like they have something important to say. He certainly had important feelings to share about his baby sister, that's for sure.

He wrote notes to my husband. "Daddy, we are going to the park. Back soon. 11:00am."

He made labels for his Lego creations. "Animal. Farm. Mob. Farm."

He wrote a book called Rescue the Stuffies about all the times had been mad when B had tried to touch his favourite stuffed animals, and then he read it to her multiple times.

I didn't tell him to do any of these things, they were not part of a lesson, they are just examples of how literacy serves a purpose in real life, for social communication, for sharing information, for processing emotions, and he was learning these things in a very meaningful way.

One aspect of my classroom teaching that did actually translate well to our home education was Vivian Paley's storytelling curriculum. In my class, I would take one child aside during playtime and ask them to tell me a story, scribing as they spoke, then we would read the story to the class, with classmates acting it out as I read, then everyone's stories would be compiled into a class book. E and I didn't always get to the acting portion, but over the years I have scribed many song and stories for him! Here are two early ones from when he was age 2 and 3, and one from age 5.

By the end of E's kindergarten year, having exclusively following his own interests for many, many months, this was the type of writing he was producing. Under the British Columbia Language Arts learning standards for kindergarten at that time, I would have marked this "Exceeding Expectations."

The Duck

Pond Tree Fish Quack

I am a duck that doesn't have a tail. Fish has a tail. Ah! Now Fish doesn't have a tail. We are going to the ocean monument.

Foundational math knowledge was also achievable without formal lessons. For example, we were reading Winnie the Pooh and Piglet makes a comment about being able to draw a table with four legs visible, which E decided he needed to try. That turned into a several weeks long fascination with 3D shapes.

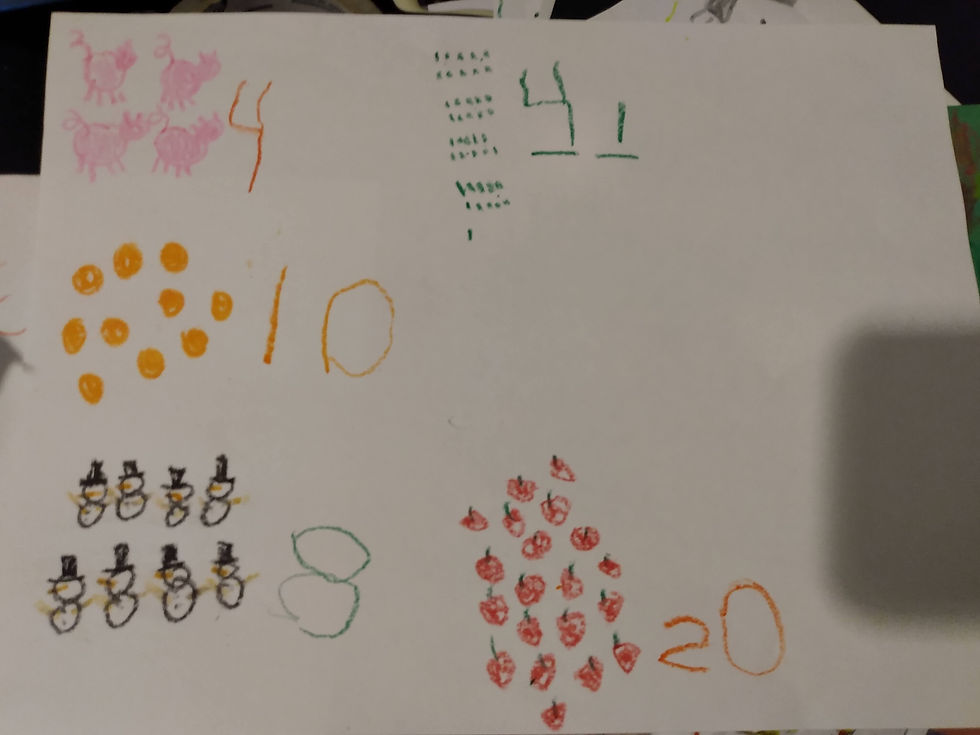

He would make himself "math activities," like this simple count and write.

He would make me activities, too.

And sometimes, he would ask me to make him a math quiz. (I couldn't correct or comment on his reversals and number formation without triggering his threat response, so I said nothing, but did make a mental note. I know that most children figure out reversals naturally by about age 8/end of grade two (he had just turned 6 at this point) so I waited it out. His reversals did correct themselves, but he still doesn't print his numbers "right," and doesn't care to learn, so c'est la vie.)

He would often create a game of good old-fashioned chalk hopscotch for us.

We baked.

He practiced sequencing by creating his own Lego "sets" and making instructions.

He created this beautiful, complex pattern for a necklace.

Once he found a work paper of my husband's around and decided to copy one of the graphs.

Again, just by being naturally intrigued by math concepts in an environment where that interest was supported and materials were available, he gained foundational math knowledge before my very eyes, without any formal instruction.

Math and literacy were my main focus for documentation, but science, social studies, art, physical activity, home economics - literally every school subject - was "covered" with a child-led, play-based, emergent curriculum.

For instance, here he decided to pick out all the stuffies he had that would belong in a cold environment and create an elaborate multi-media habitat for them.

We discovered a yellow orb weaver had moved into our front porch and watched her for weeks.

We looked on our globe for the countries our read aloud novels were set in (full disclosure, we no longer have this globe because he broke it in half in a meltdown).

He realized his highland cow stuffy was from Scotland and wanted to make him a flag (so close!).

He binge watched the show Creative Galaxy and then wanted to do every craft he had seen. Here he asked me to help him sew his own stuffy out of felt, and then he made Care Bear a birthday card.

He decorated for holidays.

He got a bigger bike and learned to "mountain bike" on the "hills" of the drainage reservoir behind our house (I say this with a laugh because I come from a place where there are real mountains!).

We watched the birds in our backyard and he drew this picture with a red wing blackbird, a ring neck dove, a blue jay, and a cardinal.

We gardened.

We went hiking.

He learned how to skip rocks.

He taught himself to swim.

He played with his sister (sometimes!).

He just played.

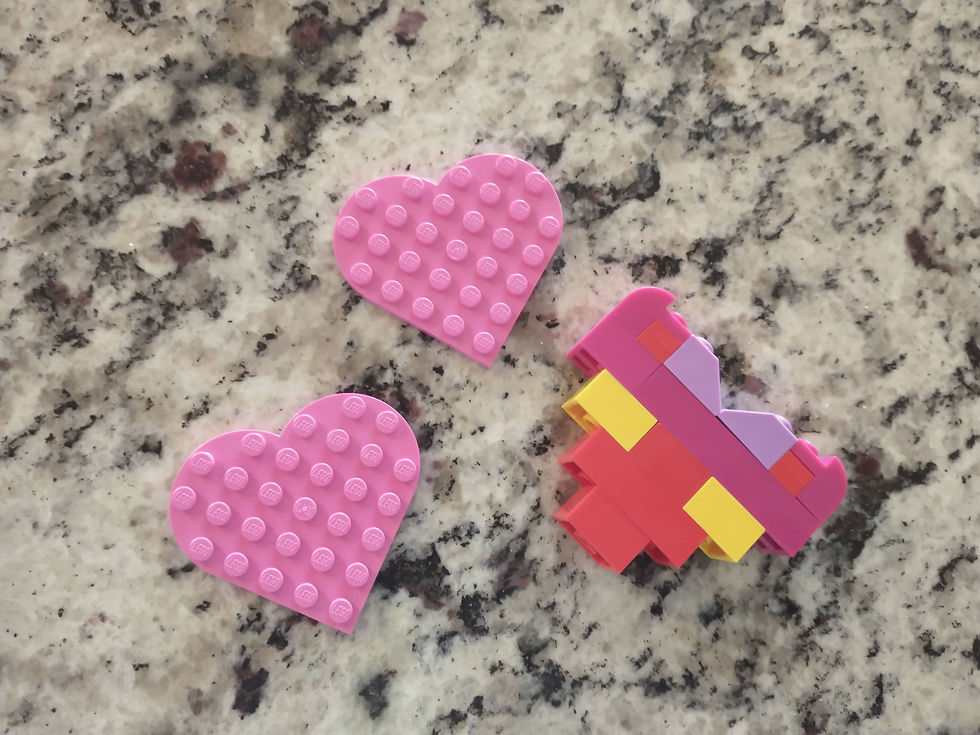

When he was feeling in a particularly affectionate mood, I learned that his love language was giving me Lego hearts.

After recognizing the beauty of self-directed education through all these observations, by the time E was six, I wasn't even trying to have "school time" at all. I had learned about unschooling by that point and was reading up on the theory behind it, sensing it was a good fit, and drawing similarities between it and my existing knowledge of emergent curriculum.

I think it's important to note, however, that at the same time as E was immersed in all this learning and growth, he was also at the start of burnout. He was able to achieve what he achieved throughout his kindergarten year because I gave him my undivided coregulatory attention for much of the day (because the baby still had several naps), and that is when I facilitated the learning you see documented in this post.

What you don't see documented here is that outside of these times when E was receiving one-on-one scaffolding with my flexible, attuned presence letting his interests lead the way, he was struggling. He was severely struggling with daily life and basic needs. I've spoken more about this in previous posts, but we couldn't brush his teeth or his hair with him ending up in a panic attack, he had stopped bathing, he was having toileting regressions and suffered from encopresis, he only ate plain starches, salty snacks, popsicles, and fast food, bedtime was a 2-3 hour physical fight, etc. When he was doing exactly as he pleased, as he was during our one on one time, he was delightful, but placing any demand pushed him instantly into fight-or-flight.

This complexity is part of what makes PDA so hard to spot. He was still learning, I marveled at his creativity and perception, and then it could switch to violence so quickly. Adding to the complexity, I know now that in addition to E being autistic, he is also intellectually gifted, so that makes him 2E, or twice exceptional. 2E kids have particularly complex and "spikey" profiles with very asynchronous development. We knew he was SO bright. I was documenting all his amazing learning, and yet he was also breaking down in so many ways.

When we learned about PDA over the summer and consequently lowered all demands, including deregistering him from first grade at our neighbourhood school, we committed to unschooling 100%. At this point, having been given the opportunity to rest and just be, he went into full burnout. He didn't leave his room for months. He only played Minecraft. All the basic needs I mentioned before continued to be an issue or got worse. But, the aggression disappeared.

Unschoolers often talk about a period of "deschooling" when a family first switches to unschool; everyone in the family needs space to spend their time however they wish in order to recover from any school trauma, to rest, and to find their way to their interests when the time is right. For us, because we fully committed to unschooling at the same time as we found out about PDA and radically lowered demands, including screentime limits, E's "deschooling" phase overlapped with the apex of his burnout crisis. He did nothing but play Minecraft and watch Minecraft videos on YouTube for several months in the fall of 2021.

I realized by this time that autistic burnout was serious and we needed to support him this way so his nervous system could recover and he could once again access basic needs. It was a huge leap of faith to commit so fully to this lifestyle, to see my vibrant, delightful 6 year old not be able to leave his room. But we forged ahead, because we had tried everything else to calm his intense meltdowns, why not try this? Interestingly, through the peak of his burnout that fall, even though we still had many struggles with basic needs, when he and I were together playing Minecraft and he was focused and regulated, the learning I witnessed through playing a video game astounded me.

As I played Minecraft with him and learned the game myself, I noticed that he wasn't "just" playing a video game; he was writing signs, he was naming his worlds, and coding command blocks where every piece of punctuation, every letter, and every number had to be precisely correct or the code wouldn't run properly. I saw him learn to make complicated electrical circuits with redstone. He figured out map coordinates and positive and negative numbers. He designed his own skins online and used different skins for different worlds depending on the themes. He created his own mobs and maps using programs like Blockbench and MCreator. He learned how to use the search bar on Google and how to decide if a webpage was what he was looking for. He learned how to download and access files on his computer. He learned how to make his own mods in Java and Bedrock. Most of the time, I was right there with him because he needed constant coregulation to feel safe, and, in the process, I was there to facilitate his learning. I googled commands, I learned how to code, I discovered intricacies in the world of Minecraft that I never imagined.

E's burnout obsession with this game opened my eyes to the beauty of video games as a form of education. At some point I think his learning through Minecraft deserves its own post! While E was in burnout and early recovery, playing who knows how many hours of Minecraft every day, he also taught himself to read and write fluently. He would watch famous Minecrafters create things on YouTube, know it was possible, and then ask me to help him figure out how. That process requires a huge amount math and literacy knowledge, as well as a huge amount of focus and imagination. We were both learning every minute of the day. Minecraft was his deep focus for about a year and half, through the later part of burnout and into recovery. Our Minecraft days allowed me surrender to unschooling. Minecraft was all he could handle at that point in time, but I could see why he was so fascinated. The opportunities were endless. I could see he was learning. So much. I knew even though his education looked so different to what I envisioned, everything was going to be ok. The learning could not be stopped.

As you can sense from all these photographs over the years, I have long been fascinated with how learning unfolds for young children. Since E was an infant, I have always documented his life, and his learning, which I've realized are one and the same. Throughout my evolution from a classroom teacher, to a homeschooling parent, to a mother of unschoolers, the documentation has always been there, and it is what allows me to now go back, reflect, and learn from the journey even more. And, an important part of documenting is sharing it with others. So here I am.

Documentation is an integral part of the Reggio Emilia Approach (the educational philosophy my own teaching was most aligned with) because it makes the creative knowledge process visible. Now, as an unschooling family, we don't have spelling tests or report cards or graded worksheets to show for E's learning, but I do have a lot of documentation. Texas is one of the states where homeschoolers do not actually need to submit any paperwork to prove we are meeting state standards (probably the only Texan-style freedom we personally benefit from!), but if we did, it would be a portfolio of documentation. This website is perhaps that portfolio! I can't help myself! Once a teacher, always a teacher, I suppose. Documenting is the main way I track E's progress. I do it out of fascination, and for my own peace of mind. I do it to make his learning visible, to him, to us, to the world.

As a classroom teacher, when I started learning about the Reggio Emilia Approach through courses and professional development, it was the stories, case studies, and documentation of other educators that made the biggest impact on my understanding. Seeing what was possible in other classrooms inspired me to keenly observe my own students, and now my own children, to notice all the learning already happening outside of formal lessons. I confidently prioritized time for play and exploration in our day to let the learning unfold in a way that was meaningful for each child. I got to know my students (and their families), learned their interests, honoured their passions, offered opportunities to build upon their existing funds of knowledge, and reflected on where we might want to go next with our projects. Although I still struggled with the practicality of shifting from a classroom teacher to an unschooling parent, philosophically, the underpinning view of the child as a capable human being who deserves to follow their interests was not a huge leap for me to make. It happened naturally and gradually as I learned more about E and his needs.

Because every child is different, there isn't a formula for unschooling. Your child's learning will look completely unique, and you may not be drawn to documenting in the same way I have been, but I hope the stories I share here will inspire you to look for the learning moments in your own home, and be in awe of the wonderful, curious, creative, determined little humans our children already are.

“The learning could not be stopped.” 💙